The final stage of the research process is usually synthesis, where ideas and concepts come together in a new form. But those syntheses rarely meet their goals if they are simply stored in your head. While there are many blockers in the writing process, from cognitive blocks to research issues, the software in your toolkit for writing should never be a block at all. I know many people who use simple word processors, like Word or Pages, for this process. But they can be buggy, and there is a better way. Here are the tools in my toolkit for writing: Scrivener and Scapple.

The final stage of the research process is usually synthesis, where ideas and concepts come together in a new form. But those syntheses rarely meet their goals if they are simply stored in your head. While there are many blockers in the writing process, from cognitive blocks to research issues, the software in your toolkit for writing should never be a block at all. I know many people who use simple word processors, like Word or Pages, for this process. But they can be buggy, and there is a better way. Here are the tools in my toolkit for writing: Scrivener and Scapple.

Scrivener and Scapple fill slightly different roles in the synthesis process. While Scrivener is a full featured writing tool, Scapple is a small lightweight mind mapping tool that lets you set out your thoughts quickly and easily. They are both cross-platform (Win/Mac/Linux [unpolished]), and have a generous trial period.

Scapple

Scapple is a quick mind mapping tool, and has been one that I been wanting for quite a few years now. In the early days of my research career, I coded up a quick mindmap tool based on a Computer Science FSA assignment I had to do in my final year. That tool was ugly, clunky, and was really a kludge. Scapple is the opposite of this. It is quick and easy to use, just double clicking on the panel allows you to create a node. Dragging nodes on top of each other allows for connections. In the words of Queensland Rail: ‘Super Simple Stuff.’ Like Briss that I talked about a few posts ago, Scapple has one purpose in mind, and it does it admirably.

Once your mind map is complete, you can easily export it to PDF, PNG or a host of other formats for later reference on devices that don’t have Scapple installed. In addition once you are at this stage you can also export it to an OPML file ready for import into Scrivener with your synthesis outline already complete. I find Scapple an invaluable tool for mind mapping, and one of the easiest tools I have used for this task. Plus it has to easily take the prize for the best price:performance ratio.

Scrivener

Onto Scrivener then. While Word and Pages, and other single document editors, may do their job for shorter pieces, they tend to be rather buggy once the file size increases. Word especially, as its method of storing the material, plus formatting, plus recent changes, plus tracked changed etc etc is prone to errors. As the document gets longer these get exponentially worse, and so for a 3000 word term paper Word is generally fine, but for a 20,000 word report, or a 90,000 word thesis, it is unacceptable.

One solution to this is to use a markup language, such as LaTeX, which I used for the majority of my Eng, Math and Psych papers. LaTeX is word processor agnostic, just using simple text files for its input, so you can edit it in anything. However, where LaTeX is excellent for rendering complex mathematical formulae, and modifying markup for export, it is not the easiest method to use. Occasionally I have had students and peers, especially in Psych, object that they aren’t computer programmers when being asked to write in TeX. The plethora of { \$ and many other codes makes it hard to learn for those who are mainly interested in text based writing.

This is where Scrivener comes in, and more. At one level Scrivener is a full featured writing device, which allows you to write easily and in a format that you are used to. But at another level it has a powerful refactoring export system, similar to working with markup languages. At yet another level Scrivener works as a consolidated research tool, allowing you to put thoughts together before writing. Another level again Scrivener allows for easy chapter and section management, letting you streamline your argument in the synthesis process. Finally, for our purposes, at a system level, Scrivener separates out its sections to different files, reducing the chances of file corruption as the document gets larger.

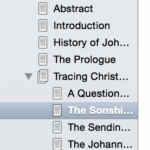

Personally I use Scrivener for almost all of my writing, be that this blog that you can see in the screenshot above, through to my conference papers, and now this new PhD thesis I am starting work on. I generally only export to Word for sharing the documents with proofreaders who don’t have Scrivener, or for final delivery. While there are many features of Scrivener that make it much easier to use than Word or other writing tools, I will quickly go through some of my favourites.

- Firstly, the nested document system allows for a structured approach to building your argument. You can create folders for chapters, and sections and then arrange your argument beneath that. This can give you a birds eye view in the Binder of where your argument is going at any time, and helps with coherence.

- Secondly, each document can be given a word limit, to help to keep you to task, and make sure that you don’t blow out your word count. This simply helps with management later on.

- Thirdly, there are a multitude of methods for being able to mark material as reference material. You can either put it in your cork board for reference, or you can annotate it inline. This means you can have some of your reference material right in front of you as you write.

- Fourthly, you can set overall word limits for a project, and also deadlines. This lets you write to task and make sure you aren’t getting too far behind on a writing project. This also helps with keeping the writing juices flowing. If you set a 500-1000 word a day target, then you can simply write to that deadline easily.

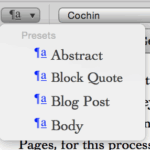

- Fifthly, it keeps the formatting out of the way. In my Scrivener templates I have a handful of formatting options, usually one for the abstract, one for headings, one for general body text and one for block quotes. The robust way that Scrivener deals with formatting means I don’t have to muck around with whatever formatting system the word processor has decided to do that day.

- Sixthly, Scrivener has a great composition mode, that blacks out other distractions on the screen, letting you just focus on the text.

- Seventhly, it allows for a regular backup routine, so that you won’t lose any of your data. Plus it writes synchronously to the file system and doesn’t require you to neurotically Ctrl/Cmd-S all the time.

- Finally, the export system, like that of LaTeX allows you to reformat your document at export time for various targets. For example, if one journal has a specific formatting system you can easily export it to their specification. Then if you are reading the same paper at a conference you can export it for a lectern friendly format as well. All without having to modify the formatting of the original document.

Overall Scrivener is a robust and powerful writing tool. It incorporates many aspects of LaTeX and other markup languages, without having the steep learning curve. But there are still a couple of downsides to Scrivener and Scapple. One is the cost, although at a total of US$60 for both apps it is one of the best investments you can make, and it has certainly saved me a lot more than $60 in crash and lost material generated heartache. In addition they are commonly on sale throughout the year, so if you want them keep an eye out. They both have a very generous trial policy as well, so you can give them a go for free without laying out the cash.

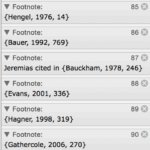

The second is the lack of a direct integration with Zotero or other reference managers. You can easily use the RTF shortcodes from Zotero, but I wish for something that was more tightly integrated.

Finally, and most minorly, there isn’t an iOS/Android app yet for Scrivener, although there is one coming soon. Which a lot of the time is fine, as for research I tend to write at my desk. There are workarounds for this one though, which I will likely cover in the future.

There we go, the final tool in my general research toolkit—although there are plenty of domain specific tools. I highly recommend Scrivener and Scapple, and I will likely do a couple more posts on both over the next little while as I want to explore specific areas of the tools.

Tell me below in the comments what tools you use for the synthesis task, and do give Scrivener and Scapple a go.

One of the best ways to get those writing juices flowing is to write regularly. I know quite a few people who simply set aside a couple of hours a day in their schedule to write. In that writing time they simply write on whatever is currently on the agenda. It could be for a paper, or project, or a conference; so long as it is writing. The dedicated time set aside helps to get a little bit done every day. However, for me this isn’t optimal, as some days with the little man I barely get a chance to write at all. For me I instead aim to write a certain amount per day, a task focused goal rather than time focused. While I don’t dedicate time, I do set myself a task every day to be written. This type of regularity works better with my schedule, and my thought processes. But whichever one you do it gets you writing regularly, and set it as a goal. As Bandura showed, short term goal setting increases the motivation for the task.[ref]Bandura, Albert. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman, 1997.[/ref]

One of the best ways to get those writing juices flowing is to write regularly. I know quite a few people who simply set aside a couple of hours a day in their schedule to write. In that writing time they simply write on whatever is currently on the agenda. It could be for a paper, or project, or a conference; so long as it is writing. The dedicated time set aside helps to get a little bit done every day. However, for me this isn’t optimal, as some days with the little man I barely get a chance to write at all. For me I instead aim to write a certain amount per day, a task focused goal rather than time focused. While I don’t dedicate time, I do set myself a task every day to be written. This type of regularity works better with my schedule, and my thought processes. But whichever one you do it gets you writing regularly, and set it as a goal. As Bandura showed, short term goal setting increases the motivation for the task.[ref]Bandura, Albert. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman, 1997.[/ref]

Ultimately though, as even William Zinsser admits ‘Writing is hard work.’ But if we write regularly, then the process comes a bit more easily, and rather than focusing on the writing task we can focus on writing style, which is arguably even more important. After all how can one edit and refine their work if there is no work there to edit in the first place. So focus first on getting words out on the screen or page and then perfecting them. Undoubtedly they wont come out exactly right the first time, or the second, or even perhaps the third, but get something out so you can work with it. In the vein of Confucious or Yoda, ‘to write a lot, you first have to write.’ Next week we will take a look at the second aspect of writing: style.

Ultimately though, as even William Zinsser admits ‘Writing is hard work.’ But if we write regularly, then the process comes a bit more easily, and rather than focusing on the writing task we can focus on writing style, which is arguably even more important. After all how can one edit and refine their work if there is no work there to edit in the first place. So focus first on getting words out on the screen or page and then perfecting them. Undoubtedly they wont come out exactly right the first time, or the second, or even perhaps the third, but get something out so you can work with it. In the vein of Confucious or Yoda, ‘to write a lot, you first have to write.’ Next week we will take a look at the second aspect of writing: style.