I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail. – Abraham Maslow[ref]Maslow, Abraham H. Toward a Psychology of Being. 1962.[/ref]

In his observations of human psychology Abraham Maslow, of the famous/infamous Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs, noted the strange bias for people to use familiar methods to complete tasks, even if they are not ideally suited for it. Abraham Kaplan more candidly expressed it as: ‘Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.’[ref]Abraham Kaplan (1964). The Conduct of Inquiry: Methodology for Behavioral Science. San Francisco: Chandler., 28.[/ref] Although my favourite visual expression comes from the older colloquial usage of the ‘Birmingham hammer.’ Nevertheless, whichever expression is chosen, the intent is clear: people tend to use the same tools to accomplish the job, even if they may be the wrong ones.

This trend is one that can be seen repeatedly throughout our society, from people and companies stubbornly sticking with outmoded methods of communication, through to DIYers using large blunt objects to persuade stuck objects to move. Maslow’s hammer appears to be all around us, and doesn’t necessarily seem to be going away. But, while the physical, technical and social implementations of Maslow’s hammer are all around us, I want to think about how it gets used from the perspective of our world views.

This trend is one that can be seen repeatedly throughout our society, from people and companies stubbornly sticking with outmoded methods of communication, through to DIYers using large blunt objects to persuade stuck objects to move. Maslow’s hammer appears to be all around us, and doesn’t necessarily seem to be going away. But, while the physical, technical and social implementations of Maslow’s hammer are all around us, I want to think about how it gets used from the perspective of our world views.

First though a brief primer on world views. Simply put a world view is in many ways the lens through which you look at and interpret the world. Mine is thoroughly shaped by my upbringing in Australia, my parental influences, my education in the sciences (Math, Psych, Chem, Biol etc), my faith, and also the minutiae of the influences from the city I live in, the politics of the era, and many more. So when we interpret information, we are inevitably interpreting it through the lens of our world view.

So what does this have to do with Maslow’s hammer? Well a bunch of our world view for intellectual pursuits comes from our training and education. Hence in this post I am calling it Maslow’s hammer, although there are some indications that it could be called other things. Maslow’s hammer resonates with me, likely through my Psych training influenced world view. This is where Maslow’s hammer highlights some of the strange decision making that we do in assessing arguments and evidence. It is probably best displayed by the slavish application of scientific method by some groups to almost every other discipline. As perhaps can be seen in some of Richard Dawkins’ twitter feed: https://twitter.com/richarddawkins/status/334656775196393473 Dawkins regularly attempts to apply his hammer (scientific reductionism) to the world around him, and upon finding a bolt (philosophy) attempts to hammer it into the hole with the same ferocity as the nails he finds.

So what does this have to do with Maslow’s hammer? Well a bunch of our world view for intellectual pursuits comes from our training and education. Hence in this post I am calling it Maslow’s hammer, although there are some indications that it could be called other things. Maslow’s hammer resonates with me, likely through my Psych training influenced world view. This is where Maslow’s hammer highlights some of the strange decision making that we do in assessing arguments and evidence. It is probably best displayed by the slavish application of scientific method by some groups to almost every other discipline. As perhaps can be seen in some of Richard Dawkins’ twitter feed: https://twitter.com/richarddawkins/status/334656775196393473 Dawkins regularly attempts to apply his hammer (scientific reductionism) to the world around him, and upon finding a bolt (philosophy) attempts to hammer it into the hole with the same ferocity as the nails he finds.

Of course Dawkins’ rigorous application of his worldview in the vein of Maslow’s hammer is on the extreme end of worldview application. However, I would propose that we all engage in this type of bias in various degrees. We each bring our experience and training to bear on the subject at hand, which is perfectly reasonable. But where the bias kicks into overdrive is where we apply our worldview to the exclusion of all other approaches.

But if you were to highlight that this bias isn’t really a bias in its own right, you would be correct. In fact it is a different extrapolation of a cognitive bias we have already covered: the confirmation bias. However, in the original post in this series I looked at the confirmation bias as a mechanism of biased interpretation of external input, in this case the bias is applied outward. Maslow’s hammer applies confirmation bias upon our internal toolkit application and finds that we tend to apply the tools in our arsenal that we are most familiar with. Correspondingly ignoring tools that we may be less familiar with, but have better utility to that situation.

So how do we engage with and steer clear of Maslow’s hammer? I believe that one of the main methods is to be polyvalent scholars and thinkers. While in the renaissance period there were some scholars such as Leonardo DaVinci who were legitimately considered polymaths (Greek: learned in much), or subject matter experts (SMEs) in multiple disciplines, I don’t think that this is the case in the modern era. While there are some in our world who can be considered polymaths, to become an SME in multiple fields is a difficult task given the high degree of specialisation required. However, polyvalence (Gk/Lt: multiple strengths)[ref]Seriously, who combines Greek and Latin word roots[/ref] I think is possible, and being well-versed, but perhaps not SME level, in a variety of topics, aids in setting down Maslow’s hammer. Rather the broad training helps with being able to diversify the toolset used, and helps scholars and thinkers alike to bring a wider variety of tools to the task. This helps with not using the wrong tool for the job. Academically speaking this is interdisciplinary work, but realistically it is all about not using a hammer where a screwdriver is ideal.

So how do we engage with and steer clear of Maslow’s hammer? I believe that one of the main methods is to be polyvalent scholars and thinkers. While in the renaissance period there were some scholars such as Leonardo DaVinci who were legitimately considered polymaths (Greek: learned in much), or subject matter experts (SMEs) in multiple disciplines, I don’t think that this is the case in the modern era. While there are some in our world who can be considered polymaths, to become an SME in multiple fields is a difficult task given the high degree of specialisation required. However, polyvalence (Gk/Lt: multiple strengths)[ref]Seriously, who combines Greek and Latin word roots[/ref] I think is possible, and being well-versed, but perhaps not SME level, in a variety of topics, aids in setting down Maslow’s hammer. Rather the broad training helps with being able to diversify the toolset used, and helps scholars and thinkers alike to bring a wider variety of tools to the task. This helps with not using the wrong tool for the job. Academically speaking this is interdisciplinary work, but realistically it is all about not using a hammer where a screwdriver is ideal.

How do you find Maslow’s hammer working in your thinking? Tell me below.

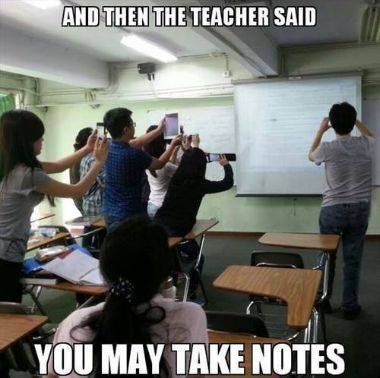

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog