When it comes to time management, organisational skills and plain old doing stuff there are a ton of pithy sayings out there: ‘to finish first you first have to finish’, ‘to do what you need to do, you need to know what not to do’ etcetera etcetera. Indeed it seems sometimes that there are almost as many methodologies for doing things, as there are pithy sayings, and things to be done. Welcome to the Friday ‘theory’ portion of the skills posts.

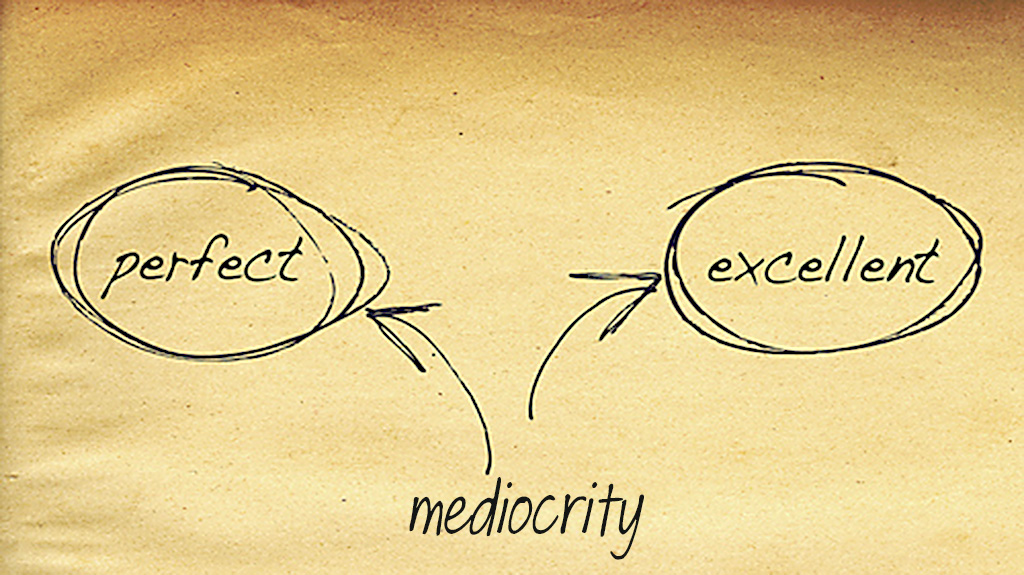

Overall the huge breadth of books and material on the topic can easily lead to analysis paralysis. I have a friend who I think has probably read every book that there is going on productivity and management and all the cookie cutter approaches, but still is absolutely hopeless at actually settling down and doing things. So what is there to do about productivity, do we simply adopt one methodology and hope it works, or swap and change between them at will? Well in many ways either of those options would be better than nothing, as usually going about our lives in a haphazard manner only leads to getting snippets of jobs done and overall lower productivity. But there are some systems that are better than others.

I must admit here, I don’t follow any one system, but rather adopt little pieces of each of them. I like the list making approach from GTD, but hate that it commonly ends up in swathes of lists without any action. I like some of the Seven Habits, from Stephen Covey, but find that a lot of the time they don’t really lead anywhere and you can end up like a guinea pig on a treadmill. So on and so forth. However, last year I read a book that sought to synthesise many of the different methods and come up with another system, the book is What’s Best Next by Matt Perman. It approaches things from a Christian perspective, anchoring theory in the Gospel, but I think it is equally as relevant to a secular endeavour and secular people. Again, I don’t adopt his entire structure point by point, but I think his overall architecture works quite well.

He has organised his method around four aspects: Define, Architect, Reduce, Execute; and yes they make a cheesy acronym: DARE. Now each of those is split up into a whole bunch of sub categories and methods, which I won’t reproduce here in whole because they would essentially be plagiarism. However, I think the four work fairly well as an overall architecture, and this is how I use them.

Define: I have a series of goals, both shorter and longer term. For example a long term goal is to do with working in Theological Academia, while a short term goal is to finish the papers I want to submit for a conference. These are written down, because if they are merely floating about in the ether then they become overly fluid and changeable. I generally revisit my longer term goals (more than a year) every year between Christmas and New Years. While I maintain my shorter term goals and tick them off as I go, and refresh these goals regularly. Longer term goals tend to be noted in a journal or note taking app. While shorter term goals are put into a task manager; more on those in the tools post on Monday. Having goals helps with knowing where the finish line is, rather than wandering aimlessly around. Plus it assists in reward based motivation and management.

Architect: Having a child has taught me that routine is relatively important. When I was at uni for my undergrad I generally just worked when I felt like it, and commonly pushed myself so hard for several months at a time that I would just collapse during holidays. Now while I still am capable of pushing that hard, it is actually far more effective to architect a routine for myself so that things get done at a good rate throughout the week, month and year rather than being in spurts and starts. To do that I have roughly mudmapped out my week. From the simple things such as the days I am at home with the little man, my research slots, through to roughly where the admin for work, college and church fits in. It is best to start with the big items first, that way you know there will be time for doing them. I tend to have things at a relatively high level, in blocks rather than to specific times, as this works well for me with changeable patterns with the little man. Others I know have a lot more set times, down to the hour or half hour. You will need to figure out what works for you. As well as planning the week, it is good to plan ahead for a 3 or 6 month block, so that things like holidays and other deadlines don’t creep up unawares. Tools for doing this include calendaring apps and task managers, which in apt timing will be covered on Monday.

Architect: Having a child has taught me that routine is relatively important. When I was at uni for my undergrad I generally just worked when I felt like it, and commonly pushed myself so hard for several months at a time that I would just collapse during holidays. Now while I still am capable of pushing that hard, it is actually far more effective to architect a routine for myself so that things get done at a good rate throughout the week, month and year rather than being in spurts and starts. To do that I have roughly mudmapped out my week. From the simple things such as the days I am at home with the little man, my research slots, through to roughly where the admin for work, college and church fits in. It is best to start with the big items first, that way you know there will be time for doing them. I tend to have things at a relatively high level, in blocks rather than to specific times, as this works well for me with changeable patterns with the little man. Others I know have a lot more set times, down to the hour or half hour. You will need to figure out what works for you. As well as planning the week, it is good to plan ahead for a 3 or 6 month block, so that things like holidays and other deadlines don’t creep up unawares. Tools for doing this include calendaring apps and task managers, which in apt timing will be covered on Monday.

Reduce: The third aspect of Perman’s approach is simply reduce. Cut out the things that are not productive in any fashion. It may be that for you sitting down and watching some TV is cathartic and helps you relax, I know it does for Gill. But if watching 5 episodes of your favourite TV show each night is causing time issues because things aren’t getting done, then perhaps its time to reduce a bit. Ultimately its up to you how much you reduce and lean out your week. But one thing to consider is how you can multitask with your time. If you take public transport to wherever you do your work then consider reading or doing some other work on that trip. Or if you walk then perhaps a relevant podcast you have wanted to listen to. This is a good way of helping you reduce without having to completely remove the things you are working on. Just make sure when you are reducing you aren’t eliminating the big things you need to get done.

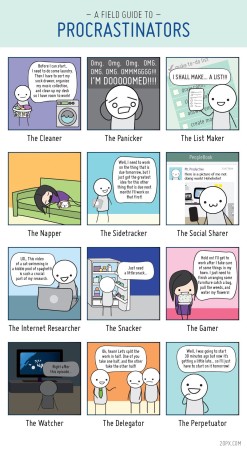

Execute: This is probably the easiest stage. You have some time set aside, now do the things you have tasked to do… and don’t procrastinate about it. While there are a bunch of different methods for doing tasks, such as reading or writing, and I’ll cover some technique to make these easier later in the series, ultimately its down to just doing the tasks. There are some tools that can make this easier, such as good task managers, the Pomodoro technique, and apps to assist with self control and defeat procrastination, and I’ll cover those on Monday as well.

Execute: This is probably the easiest stage. You have some time set aside, now do the things you have tasked to do… and don’t procrastinate about it. While there are a bunch of different methods for doing tasks, such as reading or writing, and I’ll cover some technique to make these easier later in the series, ultimately its down to just doing the tasks. There are some tools that can make this easier, such as good task managers, the Pomodoro technique, and apps to assist with self control and defeat procrastination, and I’ll cover those on Monday as well.

So how do we be productive? Well its not entirely by following a series of steps and rules. I have outlined a high level method above, which comes from Matt Perman’s book, that I highly recommend you get a copy of and read. But ultimately you need to adapt it to your own life. Perhaps a good piece of homework is to sit down and do the D-A-R-E methodology and see where you end up.

I would love to hear in the comments your own techniques for the overarching methodology you use.

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog

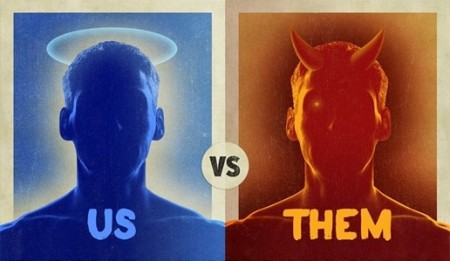

raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.

raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.