UPDATE: See end of blog post.

At times finding quotes and references in student essays, and even in academic works, can be a bit like the old gameshow Catchphrase. Although on the whole quotations should be clearly referenced, and therefore relatively easily found, there are occasionally those which send you deep down the rabbit hole and turn up only loose ends. One of these quotes that keeps raising its head is this quote attributed to Calvin:

‘But we muzzle dogs, and shall we leave men free to open their mouths as they please.’

Over the last couple of decades it has been popularised in a wide variety of sources, and generally attributed to Calvin’s works on Deuteronomy. It is understandable why it has become popular: it is polemical, expresses a censorious sentiment that is abhorrent to modern ears, and does it with a degree of vitriolic rhetoric that grabs the attention. On that basis it gets trotted out regularly to support issues of religious censorship such as this piece from the ABC on the Zaky Mallah/QandA affair: http://www.theage.com.au/comment/the-abc-wasnt-wrong-to-have-zaky-mallah-on-qa-20150623-ghvaow.[ref]Thanks to a friend for pointing this one out[/ref] However, the majority of these secondary works, if they cite anything at all, refer not to any work by Calvin, but to other secondary literature.

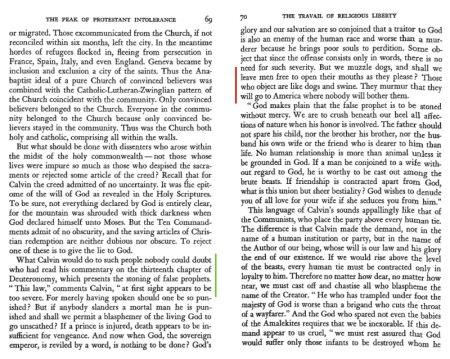

When these references are chased through the rabbit warren eventually lead back to The Travail of Religious Liberty by Roland Bainton (1951).[ref]The full text of this is out of copyright and archived on Archive.org here: https://archive.org/details/travailofreligio012230mbp[/ref] The quote itself is found on page 70 of the book, but has no citation for the quote itself (update: citations were in an end-note that was missing from my copy). For context, here is the two page spread extracted from the archive.org edition with the pertinent pieces highlighted:

The full quote reads:

‘But we muzzle dogs, and shall we leave men free to open their mouths as they please? Those who object are like dogs and swine. They murmur that they will go to America where nobody will bother them.’ [ref]Bainton, Roland H. The Travail of Religious Liberty – Nine Biographical Studies. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1951.,70.[/ref]

In the text this quote has no ending quotemark, although the next paragraph starts with a further quotemark, and so one may presume that these words are intended to be cited as a quote from Calvin, especially as the opening quotemark on page 69 reads ‘“This law,” comments Calvin “at first sight…’ It is relatively safe to take the understanding that Bainton is intending to quote Calvin at this point.

Indeed in the opening sentence of this paragraph he writes:

‘What Calvin would do to such people nobody could doubt who had read his commentary on the thirteenth chapter of Deuteronomy’[ref]Roland H. Bainton, The Travail of Religious Liberty – Nine Biographical Studies (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1951)., 69[/ref]

From this the natural reference for Bainton is that of Calvin’s words on Deuteronomy 13. However, here lies the multi-faceted problem.

Firstly, in the reference editions of Calvin’s commentaries, there is no distinct commentary on Deuteronomy. Rather there is a commentary on the Harmony of the Law, which contains many of his words on Deuteronomy. It would be a reasonable expectation to find this quote in the Harmony of the Law when Calvin deals with Deuteronomy 13, and it was my first port of call, but there is nothing there. I can find no references to dogs, canis, and muzzling can be found in any of the versions of the work I have looked at (the work from the Calvin Translation Society is the primary reference here).

The second location to search was that of the Institutes, as Calvin occasionally draws upon various passages and provides a mini-commentary to support his points. Again no references to muzzling dogs may be found in any of the four editions of the Institutes that I referred to.

The third place to search was Calvin’s sermons on Deuteronomy that he preached in October of 1555. At first this source seems to yield some parallels, with Calvin preaching regarding ‘dogs’:

‘At a word, men would have either dogs or swine in the pulpit. This is the thing that they seek for; and this is mens desires in most places; who instead of good and faithful servants to God, do choose dogs and swine’[ref]Calvin, John. Sermons on Deuteronomy. Translated by Arthur Golding. Facsimile edition edition. Edinburgh; Carlisle, Pa.: Banner of Truth, 1987., 538[/ref]

In this sermon, and the sermon preached in the following week, Calvin does talk about dogs and swine (dogges and ſwine) in a few places. However, all but one are paired as ‘dogs and swine,’ while the final reference is to the Papists and Cardinals as being dogs. Throughout his sermons on Deuteronomy I can find no reference to muzzling at all.

These three locations form the core of the material that Calvin wrote or preached on Deuteronomy. But in case I was missing something I also ran searches for ‘muzzling’ and ‘dogs’ throughout all of the resources I could find electronically (the Calvini Opera, Archive.org, CCEL, StudyLight etc provided ample resourcing). Logos, DevonThink, were used for basic searches and a custom LSA[ref]Latent Semantic Analysis is a natural language computational linguistics tool[/ref] corpus was used to see if any inferences and alternately translated words could be detected. None of these searches returned any significant results, with the majority of hits being those found in Calvin’s sermons on Deuteronomy 13. All in all I cannot find any reference to the core of the original quote regarding muzzling dogs anywhere in Calvin’s works.

However, I have another reservation about the full quote from Bainton’s book. The quote continues on to indicate that ‘they murmur that they will go to America where nobody will bother them.’ Given that Bainton is talking about Protestant religious persecution in this chapter, this indication seems somewhat anachronistic. Presuming the quote is genuine, at latest it would have been written in c.1559 when the last of the material on Deuteronomy (Commentary on the Harmony of the Law) was written, as from this quote in Vie de Calvin

Towards the end of that year [1559] they began in the Friday meetings the exposition of the four last books of Moses in the form of a Harmony, just as Calvin assembled the material in his commentary which he had published afterwards. [ref]CO 21:90. See DeBoer Origin And Originality Of John Calvin’s ‘Harmony Of The Law’, The Expository Project On Exodus-Deuteronomy (Acta Theologica Supplementum 10, 2008) for more details[/ref]

At this time the prime settlements in America were Catholic in nature. The only reference to a Protestant site that I can find is that of Charlesfort-Santa Elena in South Carolina, the site of a Hugenot settlement. However, apart from this failed settlement where may this American settlement refer to. Indeed if, as Bainton is arguing, this quote is referring to Protestants fleeing Europe over persecution (Bainton later links the Michael Servetus incident here), then it would make no sense to flee to a location that was experiencing significant religious persecution if they want to go somewhere where ‘nobody will bother them.’ This sentiment fits far better in the early-17th century, rather than the mid-16th century.

This historical tangent aside, what do we make of this quote? Certainly if one wants to convey the sentiment of religious persecution and debate, a case may be mounted from Calvin’s works. But I would argue that this quote is not a reliable source for it. I still cannot find any reference to the quote, nor any significant material on fleeing to America, in any of Calvin’s works. I have enquired with some Calvin scholars to no avail—or with some no reply.

Therefore I am turning to the broader internet, if anyone can supply the location of the quote I would be very interested.

UPDATE:

It appears that in my prejudice for trusting the validity of physical books over archive.org scans I had missed that Travails has its sourcing in end notes after the final chapter. Unfortunately the copy that I had sourced from a local library was rebound and missing the sources and index at the end of the book. Thanks to Richard Walker for highlighting this to me, see his Disqus comment for more details (unless Disqus isn’t loading again).

However, I’m still not convinced by the translation that Bainton has supplied and will blog on that later.