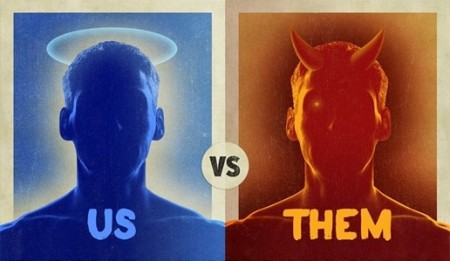

In Australia it is that time of year again… summer. Where the weather gets nicer, and in Adelaide the Tour Down Under arrives in town. Now unsurprisingly this annual event sees the seasonal rise of visible cyclists, and of course accompanying it the usual diatribes and vitriol flashing about in all directions over the topic. There are many directions that these ‘conversations’ inevitably go in, be it down the path of licensing, or psychopathic motorists, or apparent flagrant disregard for the law… from both sides. However, none of these are what I want to address in this post. Rather, I think it is helpful to look at some of the underlying factors within the cyclist/motorist interaction, specifically that of group biases and Social Identity Theory (SIT). It is especially helpful in this case because the interaction is relatively arbitrary and crosses many other more complex social bounds in a relatively equal fashion. This helps as it acts as a type of microcosm or case study that can inform much more complex interactions.

Firstly, an exceedingly brief overview of SIT and some of the biases at play. SIT was formulated by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in the late 70s and early 80s as a means of exploring intergroup relations. [Ref]Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Chicago, Ill: Nelson-Hall, 1986.[ref] Primarily SIT seeks to define groups and their relations such that there is a form of predictive capability of the interactions between the groups. At a secondary level it allows for a structured methodology for analysis of intergroup relations and conflict, the primary use for it in this situation. Since SIT’s proposal has been augmented by a series of papers that have investigated how SIT may be used to elucidate further aspects of intergroup interaction. Of particular relevance here is the work by Struch and Schwartz. [ref]Struch, N., and S. H. Schwartz. “Intergroup Aggression: Its Predictors and Distinctness from in-Group Bias.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56, no. 3 (March 1989): 364–73.[/ref] There they note some of the factors that impact upon intergroup aggression; quoting from their abstract:

Firstly, an exceedingly brief overview of SIT and some of the biases at play. SIT was formulated by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in the late 70s and early 80s as a means of exploring intergroup relations. [Ref]Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Chicago, Ill: Nelson-Hall, 1986.[ref] Primarily SIT seeks to define groups and their relations such that there is a form of predictive capability of the interactions between the groups. At a secondary level it allows for a structured methodology for analysis of intergroup relations and conflict, the primary use for it in this situation. Since SIT’s proposal has been augmented by a series of papers that have investigated how SIT may be used to elucidate further aspects of intergroup interaction. Of particular relevance here is the work by Struch and Schwartz. [ref]Struch, N., and S. H. Schwartz. “Intergroup Aggression: Its Predictors and Distinctness from in-Group Bias.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56, no. 3 (March 1989): 364–73.[/ref] There they note some of the factors that impact upon intergroup aggression; quoting from their abstract:

Perceived intergroup conflict of interests, the postulated motivator of aggression, predicted it strongly. The effects of conflict on aggression were partially mediated by 2 indexes of dehumanizing the out-group (perceived value dissimilarity and trait inhumanity) and by 1 index of probable empathy with it (perceived in-group–out-group boundary permeability).

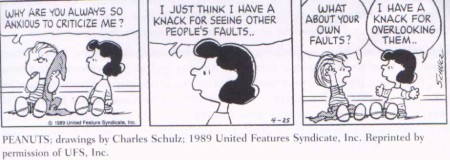

In effect they name ‘intergroup conflict of interest’ as the primary motivator, and impacted by the dehumanisation of the out-group and the permeability of the boundaries. Finally in another study by Mackie et. al. they found significant application of the fundamental attribution error within groups, novelly naming this ‘group attribution error.’ [ref]Mackie, Diane M., Scott T. Allison, and David M. Messick. “Outcome Biases in Social Perception: Implications for Dispositional Inference, Attitude Change, Stereotyping, and Social Behavior.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology – ADVAN EXP SOC PSYCHOL 28 (1996): 53–93. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60236-1.[/ref] In lieu of the longer post on FAE to come the simplified understanding is such that in-group members characterise out-group members by individual actions (and usually those that serve the in-group confirmation bias).

So how does this impact upon our little case study? Well if the motorist/cyclist dynamic is dichotomised between cyclists and motorists, as the debates ensue, then SIT can be utilised in looking at the intergroup interactions. Addressing the first of the sub factors from Struch and Schwartz, even though the permeability between groups is incredibly high, with many bicycle riders owning cars, and obviously vice-versa, the perceived permeability is exceedingly low. I would suggest that this is due to the mutual exclusivity of the means of transport, its impossible to operate both at the same time, and only a marginal percentage of cars are seen with bike racks. Furthermore the proliferation of the ‘ownership’ of the roads, as highlighted by the large number of aggressive claims to ‘our’ roads from both sides serves to further delineate the groups.

So how does this impact upon our little case study? Well if the motorist/cyclist dynamic is dichotomised between cyclists and motorists, as the debates ensue, then SIT can be utilised in looking at the intergroup interactions. Addressing the first of the sub factors from Struch and Schwartz, even though the permeability between groups is incredibly high, with many bicycle riders owning cars, and obviously vice-versa, the perceived permeability is exceedingly low. I would suggest that this is due to the mutual exclusivity of the means of transport, its impossible to operate both at the same time, and only a marginal percentage of cars are seen with bike racks. Furthermore the proliferation of the ‘ownership’ of the roads, as highlighted by the large number of aggressive claims to ‘our’ roads from both sides serves to further delineate the groups.

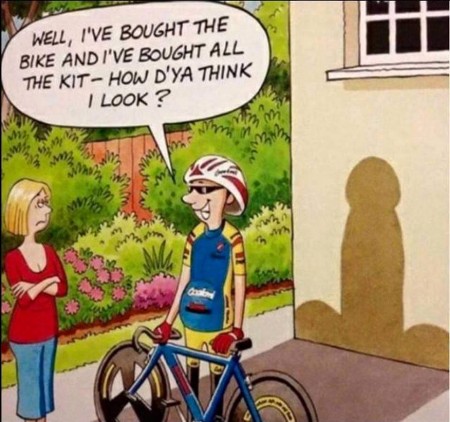

The second of the Struch and Schwartz characteristics is that of dehumanisation of the out-group, and this is extremely easy to see in the language used in the debates. Via that erudite medium of Facebook I have seen a plethora of invectives such as ‘death cage operators’, ‘lycra scum’, etc with many more that aren’t worth repeating. All of these serve to remove the person from the out-group, and replace them with a dehumanised label. For an even more prevalent example of this, see the American propaganda during the Vietnam war dehumanising the Vietnamese as monkeys (c.f. the work of Albert Bandura on the same). The last of Struch and Schwartz’ characteristics is that of conflict of interests, which in this case is the usual and predictable conflict over space on the roads.

Mackie’s applications of group attribution error can be relatively easily seen as well with the anecdotal evidence base significantly outweighing any statistical or Bayesian measures. The usual argument appears: ‘I saw a cyclist breaking the law, therefore all cyclists break the law’ or ‘I was harassed by a road  raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.

raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.

Finally it is worth acknowledging that there are a plethora of other factors at work, from confirmation biases to clustering illusions, empathy gaps and many more. However, the majority of these serve to reinforce existing group boundaries, rather than dissolve them, so while they contribute to the bigger picture it is in terms of detail rather than applicability.

So what can be done with this situation? It is all well and good to use SIT to describe an intergroup interaction, but as with many aspects of academia it is hollow if left there. One of the advantages of describing the interaction in this way is that participants in the groups get to see how their biases shape the interaction as a whole. This is where education comes into play. While educating cyclists that not all motorists are homicidal psychopaths, and educating motorists that not all cyclists are flagrantly law-flaunting dilettantes will not remove those who are genuinely homicidal psychopaths and flagrant law-flaunters, it does break down the boundaries somewhat.

This breaking down of the boundaries is important on two levels, firstly as it dismantles some of the conflict, and secondly as it removes places for those who genuinely are psychopathic or law flaunters to hide within their respective in-groups. I note that the Motorcycling Victoria is doing significantly more on the education front than I have seen the cycling and motoring groups do in recent times. See this video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3mWQJ9UOm8 There are many more applications of SIT in identifying biases and breaking down the stereotypes, such as serving to re-humanise the participants in each in-group and many more that I don’t have the time to explore here now. Suffice to say that proper analysis of the intergroup bias and interactions helps to inform efforts to resolve issues. But I would also suggest that without a good understanding of the group dynamics at hand there will be little traction in the plethora of discussions to be had.

Lastly, its worth noting that while the cyclist/motorist example is a salient one for many, myself included as I span both groups (disclaimer: motoring AND cycling enthusiast), it can readily be extrapolated to other intergroup conflict. The other swirling debates over ‘Islam vs the West’, various racial disputes, Republican v Democrat, Liberal vs Labor, liberal vs conservative, religious vs atheist, and many more all find application within the realm of SIT. Furthermore they all can be assisted in better conversation and possible resolutions [ref]Many resolutions are likely impossible, but at least not debating over useless topics[/ref] to various degrees by identifying the intergroup conflicts and seeing the origins and reinforcement of the biases present.

What do you think? Weigh in on the comments below.

Furthermore this is only exacerbated when it is brought into a social setting. While the nature of the FAE is powerful on an individual level it is stronger again amongst groups. The expanded bias, creatively named Group Attribution Error, sees the attributes of the out-group as being defined by individual members of that group. We met this bias briefly in the post a couple of weeks ago on Cyclists vs Motorists and Intergroup biases. This is further expanded again with Pettigrew’s, again creatively named, Ultimate Attribution Error (one must wonder where to go after this). While FAE and GAE look at the ascription to external and out-groups primarily and discard most internal and in-group data, Ultimate Attribution Error seeks to not only explain the demonisation of out-group negative actions, but explain the dismissal of out-group positive behaviours. Interestingly many of the studies that support Pettigrew’s Ultimate Attribution Error look at religio-cultural groups as their case studies, such as the study by Taylor and Jaggi (1974), or later studies on FAE/UAE and suicide bombing (Altran, 2003).

Furthermore this is only exacerbated when it is brought into a social setting. While the nature of the FAE is powerful on an individual level it is stronger again amongst groups. The expanded bias, creatively named Group Attribution Error, sees the attributes of the out-group as being defined by individual members of that group. We met this bias briefly in the post a couple of weeks ago on Cyclists vs Motorists and Intergroup biases. This is further expanded again with Pettigrew’s, again creatively named, Ultimate Attribution Error (one must wonder where to go after this). While FAE and GAE look at the ascription to external and out-groups primarily and discard most internal and in-group data, Ultimate Attribution Error seeks to not only explain the demonisation of out-group negative actions, but explain the dismissal of out-group positive behaviours. Interestingly many of the studies that support Pettigrew’s Ultimate Attribution Error look at religio-cultural groups as their case studies, such as the study by Taylor and Jaggi (1974), or later studies on FAE/UAE and suicide bombing (Altran, 2003).

raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.

raging driver once, therefore all motorists are out to kill me.’ As with most, if not all, attribution biases there is an element of truth there, but little to no statistical significance or repeatability. So these anecdotal ‘evidences’ serve only to strengthen the out-group discrimination bias, and reinforce the in-group bias. Furthermore the inverse is true, motorists don’t self-characterise by those ‘hoons’ or criminals who kill people in accidents, and neither do cyclists self characterise by those who run red lights and knock down pedestrians. The confirmation and attribution bias flows in both directions.