During this current ‘not-plebicite’ season I have been asked several times on various social media platforms as to what my position on various aspects of the debate are. But, apart from one more sleep deprived enquiry about jurisprudence, I have decided that I won’t be posting on the topic. More than this, I am becoming convinced for a few reasons that the place for extended debate is not on social media.

Much of this has come from revisiting some research I was involved in back when Tom was the ‘first friend’ you had, and Facebook was in its infancy (ok, it was 2006). Most of this research involved evaluating hugely expensive telepresence solutions such as the HP Halo system as means of improving computer mediated communication (CMC).

Two aspects of this research I will briefly consider–and most of this post is drawn from a paper I wrote back in 2015, so some bits are dated, and it is written for academic presentation. On the upside there are footnotes 😉

Emotional Confusion

The first aspect is emotional confusion, which is often present within textual communication is often parodied in mainstream media. From the innocently worded text message being read in an unintended tone, to the innocuous social media message eliciting murderous responses. See that classic Key and Peele sketch on text message confusion here (language warning). The situations are so often parodied because they are highly relatable, many, if not all, of us have had similar experiences before. Why? Why does text on a screen elicit such powerful emotive responses, when the same message in other forms barely registers a tick on the Abraham-Hicks. Studies have shown that it is the sociality, or social presence of the medium that provides the best insight into the emotional regulation that can be so diversely represented in CMC.[ref]Antony S. R. Manstead, Martin Lea, and Jeannine Goh, ‘Facing the future: emotion communication and the presence of others in the age of video-mediated communication’, in Face-To-Face Communication over the Internet (Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction; Cambridge University Press, 2011), http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511977589.009.[/ref] Specifically in our case it is the factors of physical visibility, or more precisely, the lack thereof that impact on emotional regulation. When engaging in social interaction an enormous amount of social cues are communicated non-verbally, through facial features and mannerisms. Of course with CMC the majority of these are removed, and those that remain are relegated to the domain of various emoticons and emoji. Notably this devaluation of the majority of non-verbal social cues serves to reduce the salience of social presence, and therefore the corresponding salience of the interaction partner. It is this effect that has led several companies, including my previous employer, to invest millions into virtual telepresence systems in an attempt to mitigate the loss of visual cues and the salience of interpersonal interaction.

What does that mean? Well in essence the vast majority of social cues for interpersonal interaction are removed on social media, and it is this context that assists in evaluating the emotional content of the message. From a social identity perspective Spears et al. found that within CMC based interactions both in-group and out-group salience and bounds were profoundly strengthened, and inter-group conflict was heightened.[ref]Russell Spears et al., ‘Computer-Mediated Communication as a Channel for Social Resistance The Strategic Side of SIDE’, Small Group Research 33/5 (2002): 555–574.[/ref] Furthermore, the degree of expression of these conflicts was also heightened along with the corresponding in-group solidarity expressions. Essentially, the majority of CMC interactions serve to strengthen positions, rather than act as bridges for meaningful communication. For more on that see my post a while ago on the Backfire Effect.

Emotional Regulation

The other side of this comes in terms of emotional regulation. On this Castella et al. studied the interactions found between CMC, video conferencing and face-to-face mediums and interestingly found that not only is there a heightened level of emotive behaviour for a non-visual CMC interaction.[ref]V. Orengo Castellá et al., ‘The influence of familiarity among group members, group atmosphere and assertiveness on uninhibited behavior through three different communication media’, Computers in Human Behavior 16/2 (2000): 141–159.[/ref] But also found that the emotive behaviour was significantly negatively biased. So it is not merely a heightening of all emotions, but as Derks et al also observed it ‘suggest[s] that positive emotions are expressed to the same extent as in F2F interactions, and that more intense negative emotions are even expressed more overtly in CMC.'[ref]Daantje Derks, Agneta H. Fischer, and Arjan E. R. Bos, ‘The role of emotion in computer-mediated communication: A review’, Computers in Human Behavior 24/3 (2008): 766–785.[/ref]

Ultimately when people are emotionally confused, in low physical presence environments, they tend to react emotionally–and predominantly negatively. Hence, the majority of emotional expressions that will be found in CMC will be negative reactions from the extremes of any dialectical spectrum.

What is the outcome of all of this then? Well simply put the very mechanism of computer mediated social media interacts with our own natural cognitive biases and produces an outcome that is predisposed towards burning bridges rather than building them. And this even before any considerations of social media echo chambers have been made (thats another post for another time).

Where to?

Sure, there will be always a plethora of anecdotal counters, but given human predisposition I think there is a better way. For me that better way is in person, in a setting where we can explore any conversation at length. So, if you want my views on the majority of controversial topics out there, come and talk to me over a coffee or beer.

So what can be done about it? Well this blog post is one useful step. Being aware of the backfire effect should help us evaluate our own belief systems when we are challenged with contradictory evidence. After all we are just as susceptible to the backfire effect as any other human being. So we should be evaluating ourselves and our own arguments and beliefs, and seeing where our Bayesian inference leads us, with the humility that comes from the knowledge of our own cognitive biases, and the fact that we might be wrong. However, it should also help us to sympathise with those who we think are displaying the backfire effect, and hopefully help us to contextualise and relate in such a way that defuses some of the barriers that trigger the backfire effect.

So what can be done about it? Well this blog post is one useful step. Being aware of the backfire effect should help us evaluate our own belief systems when we are challenged with contradictory evidence. After all we are just as susceptible to the backfire effect as any other human being. So we should be evaluating ourselves and our own arguments and beliefs, and seeing where our Bayesian inference leads us, with the humility that comes from the knowledge of our own cognitive biases, and the fact that we might be wrong. However, it should also help us to sympathise with those who we think are displaying the backfire effect, and hopefully help us to contextualise and relate in such a way that defuses some of the barriers that trigger the backfire effect.

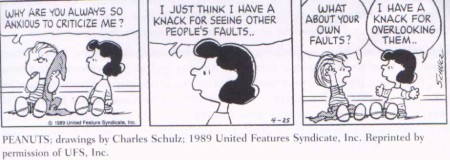

Furthermore this is only exacerbated when it is brought into a social setting. While the nature of the FAE is powerful on an individual level it is stronger again amongst groups. The expanded bias, creatively named Group Attribution Error, sees the attributes of the out-group as being defined by individual members of that group. We met this bias briefly in the post a couple of weeks ago on Cyclists vs Motorists and Intergroup biases. This is further expanded again with Pettigrew’s, again creatively named, Ultimate Attribution Error (one must wonder where to go after this). While FAE and GAE look at the ascription to external and out-groups primarily and discard most internal and in-group data, Ultimate Attribution Error seeks to not only explain the demonisation of out-group negative actions, but explain the dismissal of out-group positive behaviours. Interestingly many of the studies that support Pettigrew’s Ultimate Attribution Error look at religio-cultural groups as their case studies, such as the study by Taylor and Jaggi (1974), or later studies on FAE/UAE and suicide bombing (Altran, 2003).

Furthermore this is only exacerbated when it is brought into a social setting. While the nature of the FAE is powerful on an individual level it is stronger again amongst groups. The expanded bias, creatively named Group Attribution Error, sees the attributes of the out-group as being defined by individual members of that group. We met this bias briefly in the post a couple of weeks ago on Cyclists vs Motorists and Intergroup biases. This is further expanded again with Pettigrew’s, again creatively named, Ultimate Attribution Error (one must wonder where to go after this). While FAE and GAE look at the ascription to external and out-groups primarily and discard most internal and in-group data, Ultimate Attribution Error seeks to not only explain the demonisation of out-group negative actions, but explain the dismissal of out-group positive behaviours. Interestingly many of the studies that support Pettigrew’s Ultimate Attribution Error look at religio-cultural groups as their case studies, such as the study by Taylor and Jaggi (1974), or later studies on FAE/UAE and suicide bombing (Altran, 2003).

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog

I generally recommend that people take notes in a ‘cognitively difficult’ fashion. What constitutes cognitively difficult varies per person as well, for some it may involve reading around the subject before and after class, while for others it may be formulating interesting questions even if they are not asked in class. While for students who are learning in a non-native language it may actually mean typing verbatim, as the very act of thinking in a non-native language is a hard cognitive task. Indeed some of the students I had last year did this, and subsequently took photos of the whiteboard after class to supplement their notes. As per this amusing anecdote on James McGrath’s blog