I have been doing some musing recently on how compilations of oral traditions communicate time in linking a story together. For example if a series of stories about a person are communicated, does it necessarily matter the order that they are communicated in, and does the significance of that order change between different cultures?

Say we have a collection of stories about Winnie the Pooh, labeled Scene A, B, C and D. Temporally they occurred in a certain order A > B > C > D, but what would happen if A.A. Milne decided to compile these as C, A, D, B? While in our Western concept of time and space this would appear unnatural and confusing, I’m not sure that this is universally applicable.

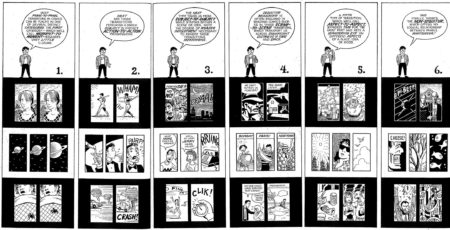

In musing about this I went back to an old book I have around on how sequential artists communicate in their specific medium: comics. Scott McCloud provides a helpful series of categories that comic artists use in communicating transitions between their panels.

In the book (and elsewhere) he notes that the majority of Western comics reflect a western concept of time, and therefore use action-to-action or scene-to-scene transitions, that are specifically temporally linked. Interestingly Eastern (Japanese/Chinese) cultures tend to also use more subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect transitions in communication–as shown here in reflections on Ghost in the Shell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gXTnl1FVFBw

However, I think that the style of communication with subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect transitions is lost on a lot of Western audiences, as they impose a temporally sequential hermeneutic on the panels.

What I have been wondering about is how this would apply to collections of oral traditions or memories. In many cases when Western trained scholars look at collections of oral tradition, such as the Gospel of John, or the book of Judges, it is presumed that the material must be temporally sequential in some form. But I have a sneaking suspicion that this is a particularly Greco-Roman concept, and that quite possibly the Hebrew/Jewish concept of time is more along the subject-to-subject and aspect-to-aspect line.

This, I think, would significantly change how we interpret and centre the compilations of collections of oral traditions. The next question though is how does it change?

Leave a Reply